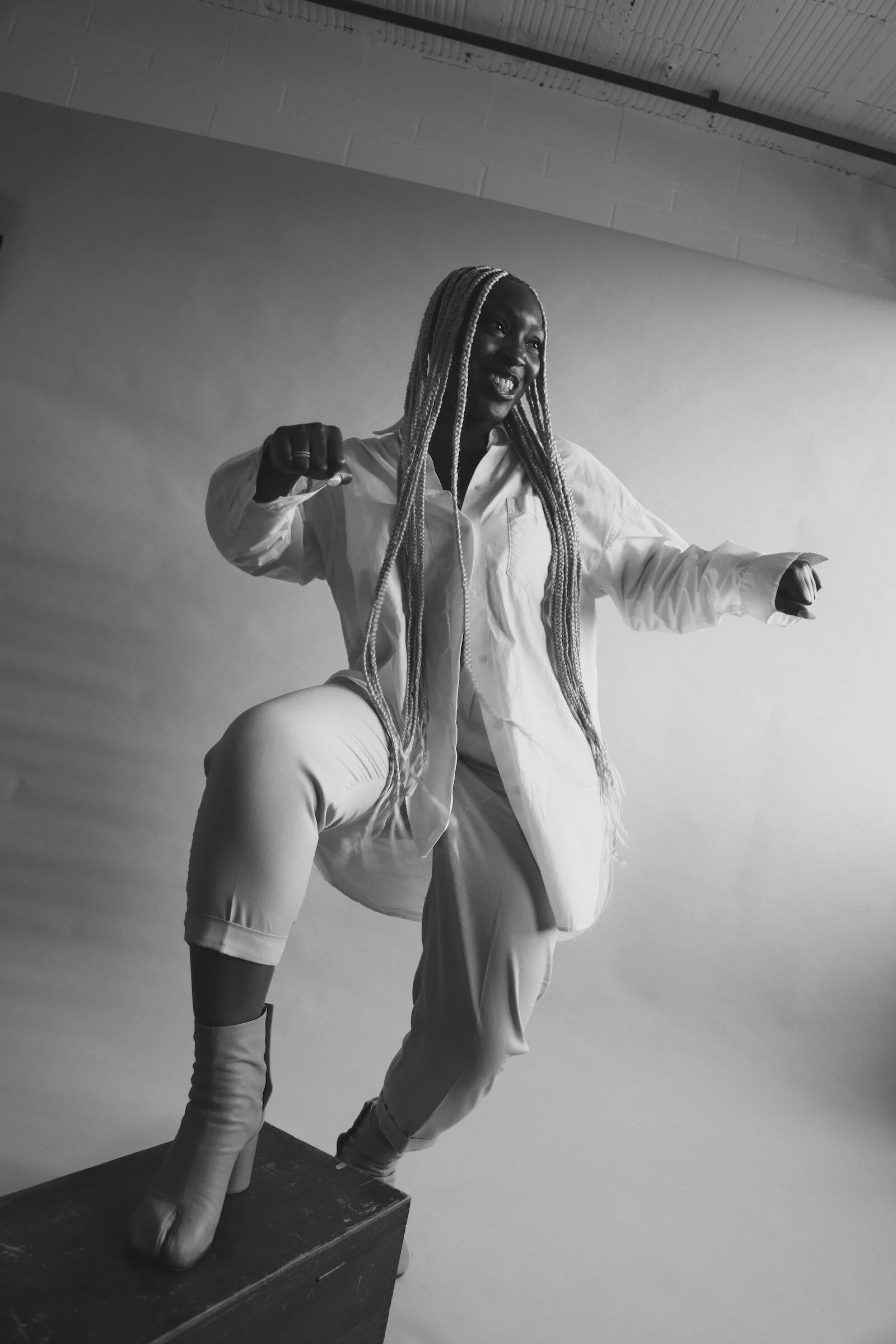

Péjú Oshin

Péjú Oshin is a British-Nigerian curator, writer and educator based in London who explores liminality in culture, identity and the built environment. She works with artists, archives and cultural artefacts to make and explore shared experiences across a global African diaspora.

Péjú Oshin

Interview: Thomasina R. Legend

Photography: Edvinas Bruzas

She began her career in 2015 as part of the first group of Young Freelancers at the London Transport Museum and went on to freelance on many projects. From there she became an Assistant Curator at the Tate in 2018 and has since been promoted to Curator.

Her work to support young and emerging artists and cultural producers is done through the Workshop Artists in Residence programme and large-scale events such as ‘ASSEMBLY 2019’. She manages the Young People’s Programme, which delivers in-gallery and online events, and she’s developed the Tate Collective Producer programme. Notable works include curating live performance Stillness (2020), Barbican’s First Young Curators’ Group (2019-2020) as well as delivering a number of public-facing events at Wellcome Collection in response to exhibitions such as ‘Living with Buildings’ and ‘Being Human’.

In 2019 Péjú completed her PgCert in Academic Practice in Art, Design and Communication at UAL and in that same year received her status as an Associate Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (AFHEA). She also holds a role as Associate Lecturer at Central Saint Martins currently teaching on the Graduate Diploma in Fashion and previously on the MA Applied Imagination (2018 -2019) as well as guest lecturing on the MA Arts and Cultural Enterprise at the school. Additionally, she was a visiting critic at the Royal College of Art for the School of Paintings 2020 Graduate show. Most recently she was shortlisted for the Forbes 30 Under 30 Europe list in the Arts & Culture category and published her first collection of poetry and prose Between Words & Space (2021), which explores performativity, a fear of vulnerability both in public and private spheres and relationships in their varying complexities through the nuances of culture, liminality and where we find home.

It feels great to have you here. It feels so light, lifted and positive and I am just so happy and incredibly excited to talk with you today. I am super excited, too. Thank you for having me.

Your work contributes to making more marginalised groups visible and, in that work; the word ‘make’ has great value and meaning to you. Can you shed light on why and how you utilise that word in your creative practice? I love that we’re starting with this. [laughs softly] Yes, love this. The word ‘make’ is very special because I love language and the multiple ways in which we can make meaning by interrogating it. For me, it is the opportunity to give life to something and take it beyond its current iteration. When I think about the idea of ‘making’, I think about the context; what is it that you want to make, where do you want to make it? How do you want to make it and sometimes even where do you want to make it? These questions all open a world of possibilities. When you think about it, we’re constantly making, creating; we are making meaning of things, we’re making space, making connections. Everything starts with this desire to make and to build something.

So, naturally, that is where I also begin, with the word ‘make’. From there, I build it up and get lovingly caught in the use of all these construction type words. When we use blocks or Lego, we wonder how many configurations can we get from it? From that point on, it’s seeing how far you can push something, where it can go, how expansive it can become, and we follow the journey through.

My background is in architecture and design so ‘making’ has always been a part of the process, even in the context of the work I do in art. It is to make something whether it's a physical thing or space in which ideas can be explored. It is all about this construction of something and the beautiful part of the process that allows you to follow it through.

How did you get into curation? How did you come to work at the Tate? I have been at the Tate for about three and half years now. Being a curator wasn't my initial plan because I never knew such a career path was available to me. I originally wanted to be an Architect, and I have always been fascinated with beautiful things, historical objects, people and narratives. Curators get to bring each of these together and package it into a presentable format for specific groups and general audiences.

I started thinking about exhibition-making before ever thinking about the context of the museum. For example, there is museum space and there is gallery space and both function in different ways. I thought about themes and narratives and if I wanted to commission an artist, what would be the brief?

I thought about things borrowed from my design education. For me there was always an element of building something which was public facing because I had studied architecture and interior design. I remember at university discussions about architecture being the most public and pervasive of all the arts, of architecture as an art form. Therefore it’s still such a big part of my practice now and why it still makes reference to buildings and homes.

Once I graduated, I worked in a small design team for a bit, working on all kinds of commercial projects but I realised it wasn’t for me. I think it was key that I did a few internships first then I moved on to a couple of different places. One of the last at which I worked, before doing the career switch, was working on new builds (gentrification) and I remember I was tasked by the practice with painting paint samples. I remember having painted eight different shades of white and I thought to myself, ‘No, this is mad’ (laughs out loud). I appreciate it now in thinking about how light works with room. At the time, I thought it was crazy because I had written my dissertation on the effects of gentrification and its impact on social housing, and it felt like such a conflict of interest for me. I decided I couldn’t do it anymore and I quit.

After that I spent a lot of time thinking about what I was going to do next and came across this volunteer project, which was happening at the London Transport Museum. They were focusing on the built environment in a twelve week-long project for young people. I applied for the project and got accepted. At the time they happened to be developing a programme called the Young Freelancers, which was aimed at making sure that the heritage of the museum’s sector was more diverse because typically it’s a very white, middle class, female-heavy sector. You may notice when visit museums and galleries the audience also skews towards white and middle-class too. So, the facilitator of the volunteer program encouraged me to apply and I became part of the first group of young people to join that scheme. Interestingly, the scheme has gone on to be replicated by lots of other London museums. I suppose you could say that’s how I got my foot in the door working in museums and how l decided to study museum education. As I started to do more freelance projects, I was able to focus on curation more, which allowed me to explore a lot of ideas.

So how would you explain your practice? What do you say to people who probably wouldn’t understand? It’s very interdisciplinary, meaning I borrow from my three main pillars being my curatorial, writing and educational practices. I have started to look at curatorial practice as being a facilitator of sorts which borrows from education. It is very much about holding relationships and again creating and making space. The idea of being a curator has become very expansive over the past ten to fifteen years - it has changed and it’s still changing, and it allows for a healthy dialogue with other disciplines which suits me perfectly. Working with and for artists is key, I see my role as supporting their vision and growth. I’m a sounding board where I ask the important questions and make things happen. My writing serves the purpose of reflecting on the now and imagining into the future in thinking about the experiences of a global African diaspora. As well as creating memory and legacy for the artists I work with, it is an opportunity to ensure they are embedded in an art historical canon, which historically excluded many. There are two elements to my curatorial work which are: 1. Exhibition making 2. Public programming (talks, workshops and that type of thing). Both play pivotal roles in supporting the artist’s career. So, for me it’s about being a facilitator who looks for an opportunity to examine an artist’s career at any one moment in time to see how I can support them and help them take next step in their practice. It’s always my goal to help those unfamiliar with an artist to better understand their practice and work by creating narrative and telling the artist’s story.

How do you find your artists? Do you research them or do they reach out to you? Honestly, it’s a mix. It often happens through relationship with artists and art collectors and the creative network. People make introductions naturally in this circle. Managing your time is crucial because it can become overwhelming. If I can give you time to listen while you talk through your project, I’ll be able to determine if I can support you directly or if I can signpost you to someone else better suited to help you.

I read that there are four key foundations to what you do: people, places, spaces and make. Would you detail how and why they’re so important? Let’s start with people because without people there is nothing, so you know that’s the first kind of reason why, because for me, connection is so important that’s why I love to spend as much time talking to and connecting with people. Meeting and just hearing about them, what their experiences are, what motivates them, what keeps them up at night? I love to hear all those details because I think very often, we get consumed with all those very surface conversations and I think very specifically when we’re working in a context of arts or creativity we can’t afford to deal with the surface. The depth is really important because that is what people connect with, that is the reason why people walk into a gallery space and they see a painting and start crying because it’s something that connects with them on that very deep and spiritual level giving it the core as to why people are so important because it actually kind of says what people actually make and then when we talk about place, where do you belong and that is also connected to people, where do you belong, where do I belong and really thinking about your placement and where do you want to be placed and you know I think it’s integral for people kind of even know that or to kind of I suppose be comfortable in the journey and getting to know that and then space of course you know thinking about architecture, thinking about geographical spaces, all these things add to very much become part of the fabric of our stories so that’s why those things have come to become four key pillars for me in thinking about how we get, how we go about building these worlds around us because it is just very important.

Speaking truth into your existence forms a great part of your life’s motto. Help us understand this more clearly. As an adult I realised a lot was projected on to me and I internalised it. People try to tell you who you are, what you should think, how you should feel and though sometimes they mean well, it can have a negative impact on you. I needed to discard all that and look at the core elements that make me who I am. It’s been grounding for me to do this. Whenever I lecture, I start with a slide detailing these core elements which feed into my work and my everyday life. It was important to identify these to experience and embrace stability and security in myself.

How much of a role does visibility and representation play in creating awareness for marginalised communities? How important is visibility and representation for you as a curator? It plays a huge role. Sometimes the depth of the work of certain artists can only be fully understood by another person of colour which speaks to my approach of building meaningful relationships with artists and going beyond the surface. Artists create - sometimes challenging - and powerful works. Not everyone will get the work as it may serve a purpose of speaking to a specific community. It’s crucial to know from where the work springs, to understand the motivation of the artist in telling this particular story and to represent them accordingly.

What are some of the challenges that come with trying to bring visibility and representation to art? One of the biggest challenges is the fact that most cultural institutions are still predominantly white. Issues which impact people of colour are sometimes downplayed as when an institution believes itself to be liberal, we sometimes fail to get to the route of the issue. Making change on issues surrounding race and representation takes a lot of emotional labour which shouldn’t be held by us. It causes discomfort and sometimes great insecurity for those who have always found it easy to occupy and navigate these spaces as they perhaps fear being sidelined or seen as redundant. Change is necessary and we must make space and give room to different truths and narratives.

Being a creative person is not easy. How do you take care of yourself mentally, emotionally, physically and spiritually? I haven’t always been the best at this but these are habits I am reforming and building now. One thing I have invested in, and I call it an investment because I do very much see it as such is seeing a therapist weekly. She’s a black woman who understands my cultural context. It’s important to speak to the small and medium- sized things, which left unchecked, can spiral into something huge. Historically there has been a stigma in some of our communities around speaking about our mental health openly and so I do this not just for me but those that come after me, too. I meditate, I pray, I exercise, I get my nails done regularly and pre-pandemic travelling, especially solo travel. But one of the key things now for me has been getting enough sleep. I really understand the value of a good night's rest now. I put my phone on silent, set it on automatic and I don’t take calls after 10pm because that’s my wind down time and my phone goes onto ‘do not disturb’, until 6am along with a screen time setting to lock apps. I really enjoy food and try to eat well and try to enjoy the little things.

As creatives we all have challenging moments, low moments. What would you say have been some of yours on your creative journey? Honestly some of the low moments were when I was initially starting out and this is so funny because I was recently talking to my brother about some of these experiences coincidentally yesterday.

When I had just graduated from university, I was so excited to start my career. I was applying to all the design agencies, and I was interested in working on projects for fashion retailers and department stores that included elements of branding as I loved the need for user data and profiles to create these spaces. As students, we were encouraged to ring the agencies and represent ourselves and those conversations went well resulting in them asking me to send my CV. I would see that the head designer or director had viewed my LinkedIn profile and would follow up a few days later if I hadn’t heard from them. But the company or agency treated me dismissively when I called again and the vibe, which had previously been so positive, had changed. This happened around twenty plus times, and it was because they were predominately white. Their staff pictures told the story, and it was heart-breaking. Still is.

I feel deeply for that version of me who worked incredibly hard and just wanted to work on amazing projects and contribute to how the world functions. It’s painful to be rejected. I’d felt the heaviness of being the only black girl in my classes at university and the lack of understanding of concepts from a fairly homogenous faculty.

People got jobs even though my work was better than theirs. Things got tight financially after graduation and my self-esteem plummeted. I wondered if I wasn’t good enough and why people didn’t want to work with me. Is it something I’m doing? It leads you to think the world only rewards difference when certain people, who didn’t include me or people that looked like me presents it. I remember last year looking through my inbox folders and I saw all the applications I sent, there were hundreds of applications. It was a rough period and created a lot of anxiety and low mood, which I didn't have the language to identify at the time. Now I see it as part of the journey in getting me to where I am now.

Your book ‘Between Words and Space’ is a wonderful gift to the world. What inspired you to write it? Thank you. During lockdown I was doing these writing exercises everyday which, funnily enough, I haven’t done recently because outside is open, and we are out here so that was the catalyst. I wrote every day because there was a need to hear myself in a different way as I continued to think about language and what those words meant to me. Another key thing in some of these works and within my practice is shared experiences across the diaspora. I really wanted to put together a collection of works, which spoke to some of the things that we have all experienced, things that are relatable and just see how that resonates with people. It was also me doing something for me, to put it out and see how it goes.

What’s the core message you want people to take from the book? I think the key thing was around healing. Healing is important because we are all always healing from something, and the pace of that healing varies from person to person. If people can relate to the sentiments in the work and start or continue their own process of healing, be it in dialogue with themselves or others then that makes me happy.

Talk to me about liminal spaces and navigating through as creative people. In architecture, liminal spaces are defined as "the physical spaces between one destination and the next." Liminal space is beautiful. It’s filled with so many possibilities and no boundaries. I’ve started to explore the possibility of these spaces being liberatory.

What advice would you give young people or anyone seeking the same career? Spend time speaking to people. Be confident in asking for mentorship. I struggled to do this in the beginning though I’ve gotten better at it now.

You don’t have to do it all by yourself. Sometimes people believe that you know what you’re doing, don’t need support and that you’re not trying to figure it out just like they are. But we all need to ask questions and experience these moments of learning in an uninhibited way. Learning should be an enjoyable endeavour.

What are some of your favourite quotes that have impacted your creative life to date? There’s one I have been thinking about recently which is (laughing out) “The truth will set you free but first it will piss you off” (laughing). I don’t know why but I must have been listening to Pharrell.

I remember this guest lecture at university from a designer named Steve Edge, I remember thinking how eccentric he came across and I loved it. He refers to himself as a prophet, madman and wanderer. He said something along the lines of always be dressed like you’re going to a party. That line feels important because clothing goes beyond function alone, for some of us, it is another creative outlet, and it speaks to our mood, state of being and aspirations. I say this knowing that it can be tricky to dress fully for yourself as we often face a lot of projections from our environments and those in them that make it hard to be comfortable with being visible. People will always have something to say and all we can do is control how we respond to it and so to that, I say step into your greatness now. Not tomorrow, but now.

Amazing. Thank you so much. Really enjoyed this. You’re welcome. Enjoyed it too. Thanks for having me.